CALDER X MIES

EXHIBITION Aug 20 — Oct 1, 2021

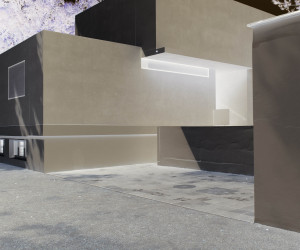

ANONYMOUS

Trinkhalle, Dessau (Architekten Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Eduard Ludwig), 1932

2 gelatin silver prints, printed ca. 1932

5,7 x 8,3 cm (each )

© Public Domain / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

JOACHIM BROHM (*1955)

L. Mies van der Rohe, Tugendhat House, Brno, Onyx-Wall, from the group 'State of M.', 2015

archival pigment print, mounted on Alu-Dibond

150 x 180 cm

© Joachim Brohm; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021 / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

JOACHIM BROHM (*1955)

L. Mies van der Rohe, Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin während der Sanierung durch David Chipperfield Architekten / L. Mies van der Rohe, New National Gallery Berlin during refurbishment by David Chipperfield Architects, 2020

archival pigment print, mounted on Alu-Dibond

71 x 90 cm

© Joachim Brohm; VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021 / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ALEXANDER CALDER (1898–1976)

Ear clips, Button and Brooch, ca. 1940s

© 2021 Calder Foundation New York; Artists Rights Society (ARS) / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ALEXANDER CALDER (after) (1898–1976)

Hammock, 1974

hand-woven Jute tapestry

310 x 112 cm

© 2021 Calder Foundation New York; Artists Rights Society (ARS) / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ALEXANDER CALDER (1989–1976)

Untitled (Abstract Forms), 1942

brush and ink on paper

78,7 X 57,2 cm

© 2021 Calder Foundation New York; Artists Rights Society (ARS) / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ALEXANDER CALDER (1898–1976)

Solomon Grundy, 1944

ink on paper, tip-mounted to mat board

28,4 x 25,8 cm

© Calder Foundation, New York; Artists Rights Society, New York; Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc.

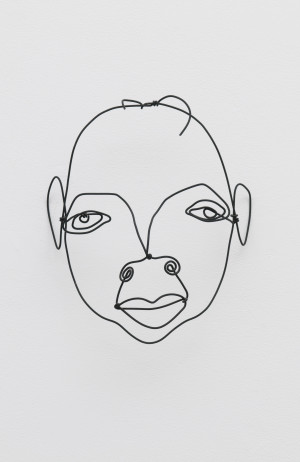

ALEXANDER CALDER (1898–1976)

Portrait of Mr. Uhlan, 1938

steel wire

27,9 x 23,5 x 12,7 cm

© Calder Foundation, New York; Artists Rights Society, New York; Courtesy Peter Freeman, Inc.

ALEXANDER CALDER (1898–1976)

Un patriote, 1975

lithograph on Arches laid paper

55,2 x 38,5 cm

© 2021 Calder Foundation New York; Artists Rights Society (ARS) / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

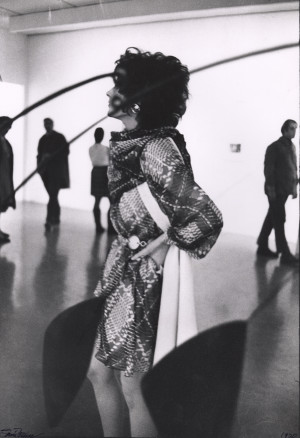

LOUIS FAURER (1916–2001)

Fashion for Harper's Bazaar, with Calder sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, NYC, 1970

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1970

34,8 x 23,2 cm

© Estate of Louis Faurer / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Alexander Calder, 1929

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1975

19,69 x 24,77 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Alexander Calder, 1929

gelatin silver print, mounted, printed ca. 1929

19,69 x 22,86 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Calder Puppets, Paris (dog on spring), 1929

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1965

19,69 x 20,96 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Calder Puppets, Paris (wire acrobat), 1929

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1965

24,13 x 17,15 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Calder Puppets, Paris (circus), 1929

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1965

19,05 x 24,13 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

ANDRÉ KERTÉSZ (1894–1985)

Calder Puppets, Paris (pipe dogs), 1929

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1965

17,15 x 24,13 cm

© Estate of André Kertész, 2021 / Courtesy Archive Consulting and Management Services LLC / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

KLAUS KINOLD (1939–2021)

Barcelona Pavillon, 1992

fine art pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, mounted on Alu-Dibond, printed later

200 x 146 cm

© Estate of Klaus Kinold / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

KLAUS KINOLD (1939–2021)

Barcelona Pavillon, 1992

fine art pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, printed 2021

ca. 40 x 60 cm

© Estate of Klaus Kinold / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

KLAUS KINOLD (1939–2021)

Haus Tugendhat, 2019

fine art pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, mounted on Alu-Dibond, printed later

150 x 147 cm

© Estate of Klaus Kinold / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

KLAUS KINOLD (1939–2021)

Haus Tugendhat, 2019

fine art pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, mounted on Alu-Dibond, printed later

156 x 200 cm

© Estate of Klaus Kinold / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

KLAUS KINOLD (1939–2021)

Haus Tugendhat, 2019

fine art pigment print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag, mounted on Alu-Dibond, printed later

60 x 40 cm

© Estate of Klaus Kinold / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

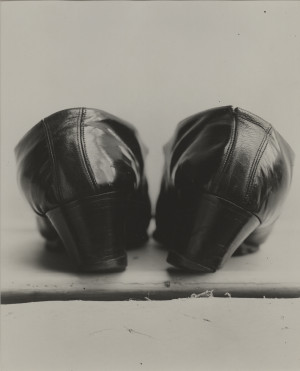

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE (1886–1969)

Stuhl MR 10, Freischwinger / Cantilever Chair MR 10, 1927

nickel-plated tubular steel frame; green cloth seat and backrest, special execution for costumer, contemporary 1930s, anonymous producer

79 x 49 x 69 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2021 / Courtesy Sammlung Gerald Fingerle

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE (1886–1969)

Armlehnsessel / Armchair MR 20, 1928

1928

82 x 53 x 76 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2021 / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

LUDWIG MIES VAN DER ROHE (1886-1969)

Stuhl MR 10, Freischwinger / Cantilever Chair MR 10, 1927

nickel-plated tubular steel frame, original red iron yarn seat and backrest, produced 1927-30

79 x 49 x 69 cm

© VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2021 / Courtesy Sammlung Gerald Fingerle

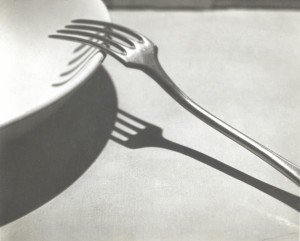

HERBERT MATTER (1907–1984)

Calder Sculpture, ca. 1939

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1939

25,4 x 20,2 cm

© 2021 Alexander Matter / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

HERBERT MATTER (1907–1984)

Calder Sculpture, ca. 1939

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1939

24,6 x 19,8 cm

© 2021 Alexander Matter / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

HERBERT MATTER (1907–1984)

Alexander Calder in his New York City storefront studio, Winter, 1936

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1960s

34,3 x 26,4 cm

© 2021 Alexander Matter / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

HERBERT MATTER (1907–1984)

Alexander Calder working on Swizzle Sticks, New York City storefront studio, Winter, 1936

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1960s

32,7 x 27,5 cm

© 2021 Alexander Matter / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

HERBERT MATTER (1907–1984)

Cirque Calder, 1943

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1960s

29,9 x 27,6 cm

© 2021 Alexander Matter / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

INGE MORATH (1923–2002)

Untitled (Alexander Calder carrying sculpture in field), 1964

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1964

22,1 x 32,9 cm

© Estate of the Artist / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, NY and Kicken Berlin

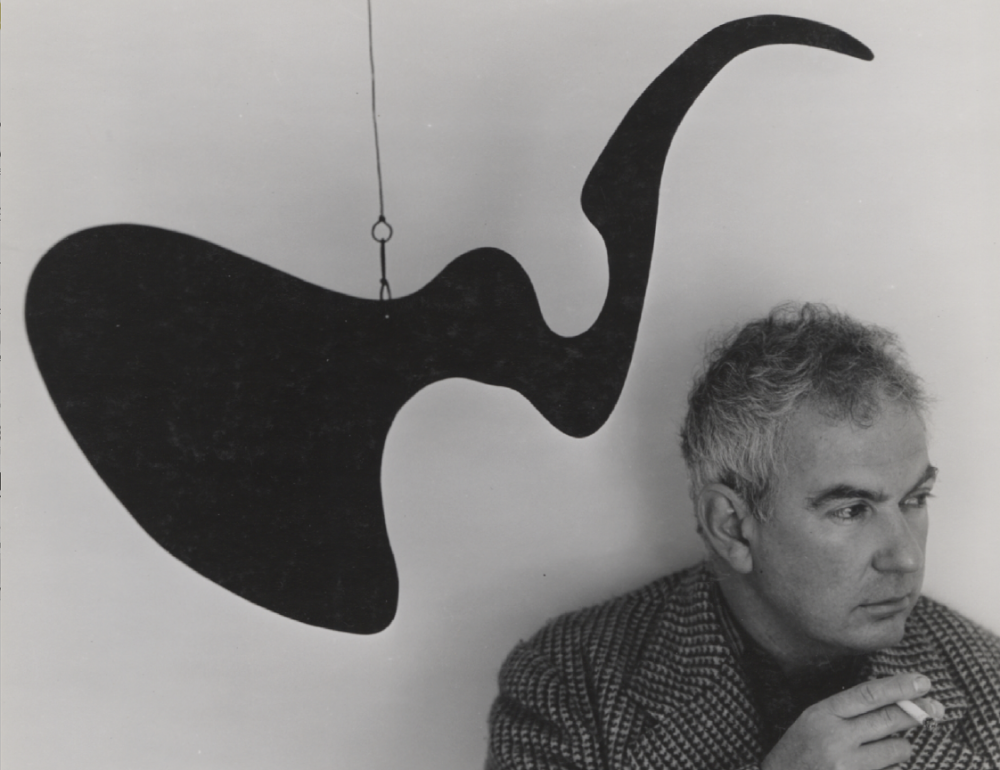

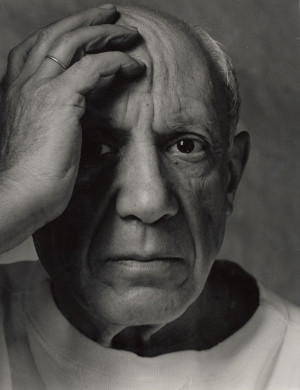

ARNOLD NEWMAN (1918–2006)

Alexander Calder, Roxbury, Connecticut, 1957

gelatin silver print, mounted, printed later

24,6 x 15,2 cm

© Estate of the Artist / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, NY and Kicken Berlin

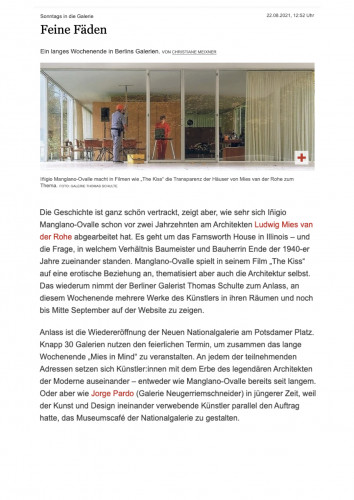

ARNOLD NEWMAN (1918–2006)

Alexander Calder, 1943

gelatin silver print, mounted, printed ca. 1943

19,5 x 22,5 cm

© Estate of the Artist / Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, NY and Kicken Berlin

Press Photo / Robert Cohen

Alexander Calder in his studio, Paris, 1946

gelatin silver print, printed ca. 1946

12,9 x 15,7 cm

© Public Domain / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

SASHA STONE (1895–1940)

Front side of the German Pavilion, World's Fair, Barcelona, by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1929

gelatin silver print, mounted on upper edge, printed ca. 1929

15,6 x 22,9 cm

© Estate of the Artist / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

JAMES THRALL SOBY (1906–1979)

Alexander Calder assembling 'Steel Fish', 1938

gelatin silver print, mounted, printed ca. 1938

22,7 x 18,9 cm

© Estate of the Artist / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

RAYMOND VOINQUEL (1912–1994)

Peggy Guggenheim at home in Venice with Alexander Calder's "Silver Bedhead" behind her, 1964

gelatin silver print, printed later

49,8 x 37,1 cm

© GDPR / Courtesy Kicken Berlin

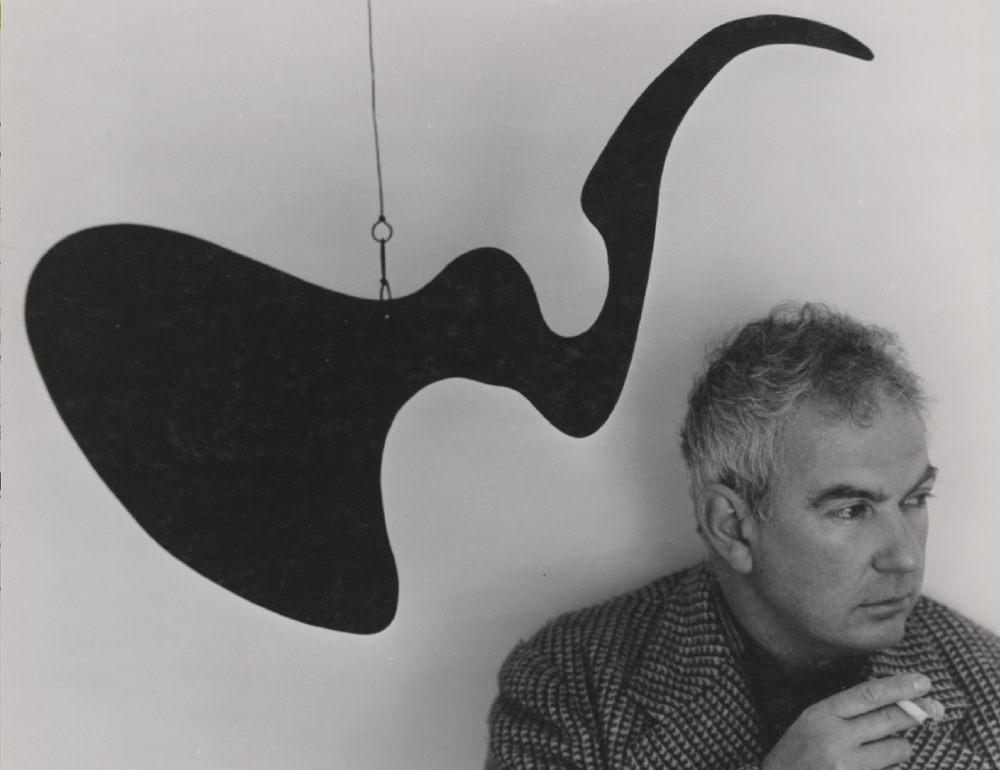

Exhibition Text

With the exhibition Calder X Mies, Kicken Berlin pays homage to two major figures of twentieth-century Modernism. Timed for the reopening of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and the concurrent exhibition there devoted to the sculptor Alexander Calder, the show is part of the collaborative project Mies in Mind, a circuit of exhibitions at thirty Berlin galleries celebrating the Neue Nationalgalerie, Mies’s unique contribution to architecture, and Calder’s extraordinary sculptural output. Much as Alexander Calder and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe explored various forms of art, from sculpture and drawing to jewelry and furniture design, so generations of photographers – including Joachim Brohm, Louis Faurer, André Kertész, Klaus Kinold, Herbert Matter, Arnold Newman, and Sasha Stone, to name just a few – entered into polyphonic dialogue with the works of these two masters. Contemporary photographers like Brohm and Kinold have approached Mies’s oeuvre with a deep awareness of the history of Modernism. Calder and Mies contributed over many decades to the development of twentieth-century Modernism in architecture and sculpture. Calder was “modern from the start,” to draw on the title of a 2021 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Born into a family of American sculptors, he turned his back on tradition in order to embrace the free spirit of modern sculpture – with graphic linearity in his wire forms, movement in his mobiles, and organic abstraction in his freestanding sculpture. His canon of sculptural forms found its way into other media as well. Drawing and graphic design, even tapestry (as in the outstanding examples included here) became natural outlets for his creativity. Jewelry design was another constant for Calder. From 1929 on he began crafting pieces using brass, silver, and gold for his wife Louisa, relatives, and friends as well as for sale. In 1945 the collector Peggy Guggenheim commissioned him to create a silver headboard for the bedroom in her Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in Venice – as seen in a 1964 photograph by Raymond Voinquel.

Calder’s work inspired many of his peers. André Kertész photographed the artist and his work as early as the spring of 1929. The two met in Paris, where Calder had lived since 1926. At the time he was already presenting his first major project – the 'Cirque Calder '– live to an interested public at his studio. This miniature, moveable circus was fashioned mainly of wire and took up a theme – the circus – that would occupy him throughout his life. The Swiss photographer Herbert Matter accompanied Calder particularly intensively with this project as well as in his daily work. He documented Calder’s creations both while they were being made in the studio as well as in exhibitions; in 1944 MoMA commissioned him to make a film portrait of the artist. Among other photographers who devoted their time to Calder were portraitists like Arnold Newman and the Magnum photographer Inge Morath. Sasha Stone, another contemporary from the 1920s, was important for both Calder and Mies van der Rohe. Stone knew Calder from Paris and helped promote his work in Berlin. He arranged the first exhibition of Calder’s work in Germany, a show at Galerie Neumann-Nierendorf in Berlin that opened on April 1, 1929. Calder later recalled making one of his first pieces of jewelry for a visitor to the show. Stone’s work also connects to architectural Modernism in significant ways. Today he is especially known for his photographic interpretations of the Barcelona Pavilion, the structure Mies designed for the International Exhibition there in 1929. Stone found congenial ways of visualizing the pavilion’s clear geometrical forms, the spatial lightness and transparency, the suspended boundary between inside and outside, and the materiality of glass, metal, stone, and water – all qualities that were characteristic of the new approach to building (the Neues Bauen). Decades after the pavilion was dismantled, it was possible to reconstruct it on the basis of his precise shots. Mies’s buildings and furniture designs have continued to attract the attention of subsequent generations of artists, offering the potential for appropriations and new interpretations as well as sober reflection. The recently deceased photographer Klaus Kinold, following his philosophy of showing “architecture as it is,” presented Mies’s buildings with precise and intensely observed restraint. He used color when photographing the interiors of Haus Tugendhat in Brno (designated a Unesco World Monument in 2001) after the villa was painstakingly renovated in the early 2010s. With sensitivity to its careful balance of interior space and furnishings, Kinold presented the iconic building as a true-to-life whole through large-format prints. Joachim Brohm, in contrast, regards Mies and other Modernist architectures as an opportunity to reflect on the past and explore its representation – and the potential for photographic dialogue – through contemporary means. He, too, probed the interiors of Haus Tugendhat. In his images, history overlaps with the present in half-transparent, half-opaque layers. Brohm also documented the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin during its renovation.

Artists

-

Bauhaus Anonymous

1919–1933

-

Joachim Brohm

*1955

-

Alexander Calder

1898–1976

-

Louis Faurer

1916-2001

-

André Kertész

1894–1985

-

Klaus Kinold

1939–2021

-

Herbert Matter

1907–1984

-

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

1886–1969

-

Inge Morath

1923–2002

-

Arnold Newman

1918–2006

-

Sasha Stone

1895–1940

-

James Thrall Soby

1906–1979

-

Raymond Voinquel

1912–1994